Today getLISBON invites series is sharing a curious article about the different readings of the Name of Macau by Ana Cristina Alves. This text ends a series of articles by the same author about the Macau Scientific and Cultural Centre and its Museum. Through this etymological exercise it’s possible to perceive part of the history of Macau, an important link between the East and the West. An intercultural dialogue that you’ll enjoy getting to know.

In China, writing is sacred, especially in the artistic incorporation of calligraphy. A given name is not only a logical but also an ontological guarantee. Almost all names have a verbal function, magically granted by the denominator. Thus, any name has a linguistic and an existential reading. But more than that: we are what language lets us be: in the beginning it was, in fact, the verb.

When Chinese parents baptise their children, they bestow upon them, like oriental magicians, the best they believe exists in their world; therefore, depending on family tendencies, names abound in families such as: dragon, phoenix, flower, wealth, beauty, health, strength, good luck, virtue, and so on. A similar situation occurs with the lands, so when we visit the Macau Scientific and Cultural Centre Museum, it’s important to understand the virtues and potentialities of the name of Macau, which was born in close association with its physical geography, for some or with the spiritual domain for others.

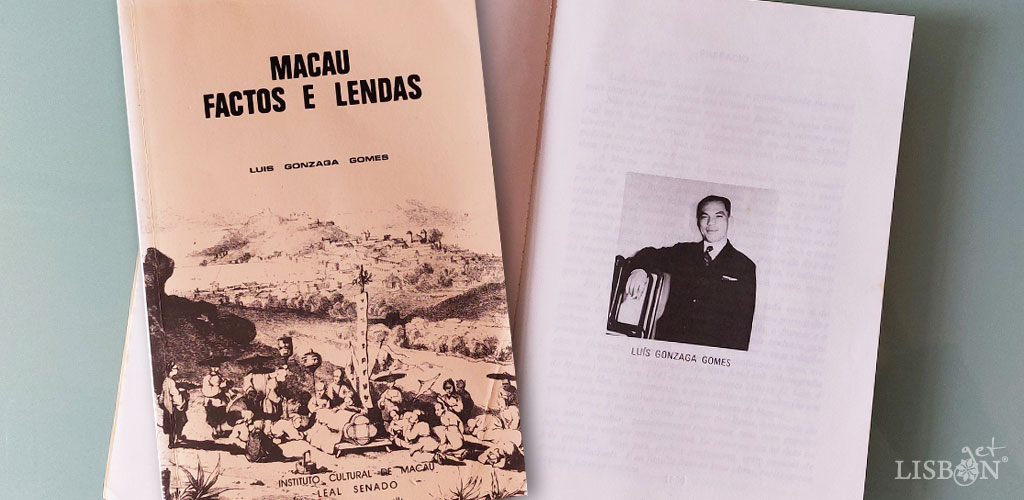

Luís Gonzaga Gomes, a great sinology specialist, says in the chapter “Os Diversos Nomes de Macau” (The Various Names of Macau) in Macau: Factos e Lendas (Macau: Facts and Legends), about the etymologies: “It is true that all these data are not very reliable and their publication is intended only to satisfy curiosity.” (Gomes 1994: 54)

By these words one can understand the true fascination of the etymological exercise that follows, since it, without any certainties, advances along a philosophical path solidly anchored in the imagination, which, with the help of geography and emotion, draws images, or better, landscapes built in a dialogue between the outside and the inside.

The Various Readings of the Name of Macau

Rural Reading

Among the hermeneutical readings rooted in etymology, it is known that, in the Chronicles of the Northern Song Dynasty (《北宋典册》Pâk Song Tin Tch’ák), the land is named “Marinhas da Chupa de Ouro” (Marine of the Gold Chupa), being chupa a bamboo recipient used to measure rice, which recalls the configuration of the region to the north of Verde Island: “金斗鹽場” (Kâm Tâu Im Tch´ông).

And in fact, a careful reading of the etymology of Macau “澳門O Mun”, a name translated as “Porta da Baía” (bay door), can assume a paddy field hue, a rice chupa, which fits the south of a country known for being the field of rice of China.

Even before the Ming dynasty (明), according to Gonzaga Gomes, other poetic names for the land circulated in close connection sometimes with the sea, sometimes with the countryside, or even with geomancy.

Marine Readings

The Macau Peninsula, seen as the junction of Taipa and Praia Grande Bay, could be either a “Mirror of the Sea” (海鏡Hoi Kèang), or a “Mirror of the Lake” (鏡湖Kèang U); an “Oyster Mirror” (蠔鏡Hou Kèang), or a “Moat Mirror” (濠镜Hou Kèang); or even a “River of the Moat” (濠江Hou Chiang).

All these marine readings prior to the arrival of the Portuguese in Macau refer to a mirrored landscape, which recalls the Pearl River in the shining silver of its best spring days.

Geomantic Reading

The calligraphic reading of geomancers names the land through what’s within, valuing the lotus configuration, which can be found everywhere, even in the isthmus of Portas do Cerco (連花茎Lin Fá Káng). For geomancers, Macau is the Peninsula they call “Island of the Water Lilies” (連花岛 Lin Fá Tou), a sacred space, which, in a strange spiritual crossing, justifies the Western terminology – the “City of the Name of God”, referred to in Charles Boxer, among other sinologists, including Gonzaga Gomes.

Religious Intercultural Reading

From here, one dives into the Ming dynasty, remembering the arrival of the Portuguese in Macau, in the “Peninsula of the Water Lilies” or in the “City of the Name of God”, as an epithet in a note by Father Gil da Matta from 1592, quoted in O Senado da Câmara de Macau by Boxer (1997:18).

The truth is that this land of the name of God meets another etymological interpretation, which is still accepted by many today: who knows if Macau was baptised as the “Bay of A-Ma” (亞媽港A-Ma Kóng ), protective deity of all seafarers, from fishermen to sailors, including traders?

“City of the Name of God” is a very plausible etymological interpretation, which has the advantage of asserting itself for its universalising vocation, since it intertwines Chinese and Portuguese readings in a happy and almost magical way, there in a sacred space where everything is found and everything is dialogue.

Geographical Readings

In addition to this miraculous interpretation, the name of Macau, read by its physical geography as “Bay Doors” (澳門 ou Mun), also seems to fit it well, since it portrays the position of the bay between the doors of the Guia and Penha Hills, being a frequent etymological reading nowadays.

Other names that Macau has been bestowed with over time cannot be excluded. For example, in the ancient Great Toponymic Dictionary of China, the doors aforementioned are called terraces, they are the Southern Terrace (南臺Nám T´ói) and the Northern Terrace (北臺Pâk Tói).

The Corruption of Macau’s Name

Finally, and already in the realm of pure guessing, where cabals and corruptions are assumed, the name of Macau appears, perhaps due to a misinterpretation of the Portuguese, derived from “Coitus of the Horse” (馬蛟Má Káu), an adulteration of (馬閣Má Kók), i.e. harbour.I believe that the Portuguese adhered, among all possible etymological interpretations for the name of Macau, to the one that suited them best, taking into account the mentality of the time and the proselytising vocation of the missionaries who then preached across the seas of the East. And the most interesting thing is that this was never denied by either the Portuguese or Chinese authorities. From an intercultural point of view, Macau was and will be “The City of the Name of God”, Portuguese or Chinese deity.

getLISBON suggests you also read the article 7 Marks of Macau in Lisbon, in which you can learn more about this city historically connected with Portugal.

| Never miss another article | Subscribe here |

Bibliography

Boxer, Charles Ralph. 1997. O Senado da Câmara de Macau. 澳門議事局. The Municipal Council of Macao. Introd. António Aresta e Celina Veiga de Oliveira. Macau: Leal Senado de Macau

Gomes Gonzaga, Luís. 1994. Macau: Factos e Lendas. Macau: Instituto Cultural de Macau

Ana Cristina Ferreira de Almeida Rodrigues Alves has a PhD in Philosophy of History, of Culture and Religion from the University of Lisbon since 2005.

She coordinates the Education Service and the Chinese/Portuguese translation area at the Macau Scientific and Cultural Centre.

She also collaborates with the Institute of Culture and Portuguese Language of the Faculty of Arts of the University of Lisbon.

She has published works on tales and myths related to Chinese culture, essays on Chinese philosophy and pedagogical material on Chinese-Portuguese translation. In 2021, she won the A-Má Prize, awarded by Casa de Macau Foundation, with the short story “Delírios de A-Má”.