The getLISBON invites series is pleased to have the collaboration of Gisela Monteiro, researcher at the Cemetery Management Division of the Lisbon City Council. In the article The Portuguese House in Cemeteries, this researcher shares with us the study she has been developing about the curious use in the mausoleums of the traditional architectural style popular outside the cemeteries.

The Public Cemeteries of Lisbon

When in the spring of 1833 an epidemic of cholera morbus caused mortality to soar in Lisbon, it was necessary to interdict the existing parish cemeteries and create adequate burial spaces, away from residential areas.

A few decades earlier, Diogo Inácio de Pina Manique (1733-1805) had ordered the selection of plots of land outside the urban area to build public cemeteries, but when he stepped down as general superintendent of police, this plan was forgotten.

Forty years later, ditches began to be dug for the burial of the victims of the cholera epidemic, giving rise to the Alto de São João and Prazeres cemeteries.

The creation of Lisbon’s public cemeteries thus preceded, by necessity, the legislation of 1835 of Rodrigo da Fonseca Magalhães (1787-1858), Minister of Business of the Kingdom, which led to the creation of public cemeteries in Portugal and prevented burials inside temples.

Thus, the families that had burial chapels inside the churches were forced to look for new solutions for their family mausoleums and the answer was in the new public cemeteries that were being created throughout the territory.

In the City of the Dead as in the City of the Living

The new public cemeteries, being in the open air and in an open space, brought novelty in the way burial markings could be made, responding to the need to make these markings last in time, eternalising those they sought to remember.

The management of the space was also different and examples of reference were sought: in 1838, the regulations and plans of the Père Lachaise cemetery (1804) were requested from Paris, a model for many of the 19th century European cemeteries and, from 1839, land plots were registered for the construction of funerary monuments in Alto de São João and Prazeres cemeteries.

Streets, sections, squares, avenues, more noble and less noble areas were created. They began with underground burial constructions, decorated with French-inspired monuments, moving on to the chapel-mausoleums, of white and pink lioz stone, which characterises the cemeteries of the capital.

These chapel-mausoleums gained more space and creativity, with great symbolic richness, thematic variations and stylistic and architectural choices that mimicked those that were being implemented in the city of the living, outside the high walls of the cemeteries.

The Appearance of the Portuguese House in Cemeteries

Among the national-inspired styles present in cemeteries, such as the Neo-Manueline style – influenced by the 19th century work on the remodelling of Jerónimos Monastery or the construction of the Rossio Railway Station by the architect José Luís Monteiro (1848-1942) – there are also the Portuguese House chapel-mausoleums.

Between the end of the first decade and the beginning of the third decade of the 20th century, these chapel-mausoleums appeared, trying to incorporate characteristics of the style that was becoming popular outside the cemeteries and which became known as Casa Portuguesa (Portuguese House).

Strongly associated with the architect Raul Lino (1879-1974)1, author of several books that achieved great popularity, precisely on the Portuguese House, this style proposed to recover characteristics and aesthetic choices of the Portuguese dwellings considered traditional, emphasising their adaptation to the terrain and climate.

From the body of theoretical and practical work left behind by the various architects who leaned into it, what passed onto the interior of the cemetery are its most easily recognisable visual characteristics and which Raul Lino himself, ironically, illustrates in the book Casas Portuguesas: alguns apontamentos sôbre o arquitectar das casas simples (1933) – freely translated: Portuguese Houses: some notes on the architecture of simple houses – as being the usual request of those who saw in the Portuguese House a purely aesthetic value:

“I want a cute house, with a wicket door, with little roofs over the windows and a panel of tiles with a lamp.”

1 Having begun his studies in England and completed his architectural training in Hanover, at the studio of Prof. Albrecht Haupt, who was doctorate in Portuguese Renaissance architecture, Raul Lino travelled around Portugal by bicycle and visited Morocco, studying and designing what he saw, incorporating the various influences into his buildings, always concerned – as he has largely expounded in his books – to adapt his creations to the environment and climate in which they were built, making the most of the sun’s orientation, warning about the direction of the winds and the level of rainfall, and taking advantage of the nature of the terrain in favour of the building. One of the most cited examples to illustrate this concern is the Cipreste House – his own family home – which, having been built in an old quarry in Sintra, took advantage of the terrain and orientation to construct what he himself describes as “a cat curled up in the sun”.

The Portuguese House as a Mausoleum

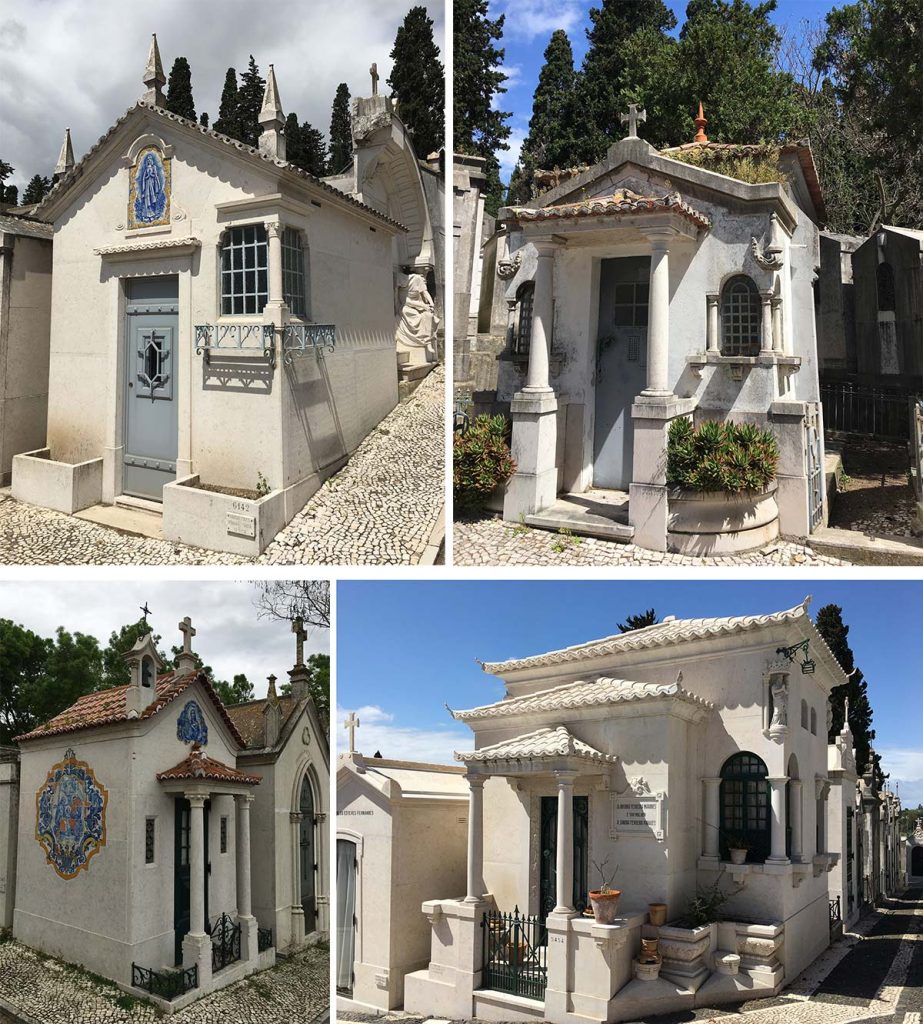

In the seven municipal cemeteries of Lisbon2 we can find around fifty constructions that can be considered Portuguese House Mausoleums, mostly built between 1923 and 1933, with occasional constructions before and after these dates.

Their main characteristic, present in all the mausoleums of this type and which distinguishes them from the others, is undoubtedly the presence of the roof covered with roof tiles; but also very popular are the porches, the wicket doors, the windows – a rare characteristic in mausoleums of other types -, sometimes even with lace curtains inside, and the presence of tiles.

One can also find flower boxes flanking the door and iron rods (or vestiges of them), projected from the wall, where lamps are hung, some of which have disappeared with the action of nature.

Considering that these are houses-of-death and not houses-of-life, characteristics typical of the graves of a Christian cemetery were added to them: crosses on the rooftops and the presence of bells.

Although this list of features seems clear, it’s worth looking in more detail at some of these components.

2 Alto de São João (1833), Prazeres (1833), Ajuda (1786), Benfica (1869), Olivais (1897), Lumiar (1887) and Carnide (1996).

Between the Symbolic and the Real: Roofs and Porches

As mentioned, the main characteristic of the Portuguese House in cemeteries is the roof, which is covered with the traditional ceramic tile. However, not all the mausoleums do it in the same way: some choose a complete covering with red ceramic tiles, immediately transmitting the effect that some visitors call “Portugal dos Pequenitos“3, which bring us to the buildings made outside the cemetery, with the red of the tiles contrasting strongly with the light tones of the stone, mostly lioz, used in the cemetery. The other option is for the roof to use the same stone used in the construction of the grave, but carving it in the shape of a roof tile, differing from the previous roofs in colour, creating a blanket of simulated, symbolic tiles.

A similar situation occurs with the porches. Being a present characteristic in almost all the studied Portuguese House mausoleums, the porches are over the door, extending in front of the mausoleum and supported by columns. They may be of greater or lesser depth, but, since the interior of the mausoleum has a mandatory minimum dimension from front to back due to the standard size shelves to place the coffins, the space needed for the porch adds to the building plot, leading to a purchase of larger, more expensive plots. Thus, in some cases, an option was chosen that allows keeping a merely symbolic, vestigial porch, with a narrow strip of tiles – of ceramic or stone – over the door, not forcing the acquisition of a larger plot of land, but maintaining the function of the porch – which protects and comforts those who visit or inhabit the house – but in a symbolic way.

3In reference to the Portugal dos Pequenitos park in Coimbra, considered to be the first Portuguese theme park, built by the architect Cassiano Branco (1879-1970) and inaugurated on June 8, 1940, containing small replicas of national monuments and houses considered typical of certain areas of the country.

Between Decorative and Protective: Tile Panels

As part of the image of what we know as the Portuguese House, the decoration using tile panels and friezes is also present in the mausoleums. Besides the existence of side panels of considerable dimensions and painted, for example, with motifs alluding to death, in which angels lift the souls towards Paradise or depict wakes, there are also small panels, usually placed on the front façade of the mausoleums, on the porches, painted with figures of saints – as in the lyrics of the 1953 song, popularised by Amália Rodrigues A Casa Portuguesa in which it refers to the existence of “a Saint Joseph tile panel”.

In a detailed analysis, case by case, it was concluded that, in the majority of the identified situations, the saint represented in the panels is the patron saint of the first owner of the mausoleum or of its first occupant. Representations of Saint Joseph, Saint Amelia, Saint Charles Borromeo, Saint Christine, Saint Anthony – to name but a few of those identified – are found adorning Portuguese House mausoleums where the ashes of a José, an Amélia, a Carlos, a Cristina or an António are placed.

We may say that, besides being decorative, the tile panels and the saints represented on them were chosen with a protective purpose.

The presence of the Portuguese House in cemeteries is a subject still under study and with much to discover, besides what we share here.

We invite you to visit the cemeteries of Lisbon and discover these delicate and original constructions and the secrets they have to tell.

| Never miss another article | Subscribe here |

On these topics, getLISBON suggests reading the articles:

– Historic Cemeteries: Eerie Places or Open-Air Museums?

– Ajuda Cemetery, the Third Historic Cemetery of Lisbon

– Traces of the Trinas Case in the Prazeres Cemetery

Gisela Monteiro

Master’s Student of History of Art at FCSH NOVA and researcher at the Cemetery Management Division of the Lisbon City Council, Gisela has participated in several national and international conferences, presenting and publishing on topics related to cemeteries.

Among other themes, she is currently investigating the stylistic choices in Portuguese cemeteries – especially during the first half of the 20th century – and the 19th century Autopsy Houses.

She runs the Mort Safe website for the dissemination of heritage, culture and art of the cemeteries.

She can be contacted via Facebook, Instagram and email: [email protected]