Do you remember the figure and cries of the varinas of Lisbon (Lisbon’s fishwives)? Perhaps you only know them through the countless allusions and representations that evoke them. In this article we’ll tell you about their origins, characteristics, what made them so popular, and other curious facts that you will enjoy recalling or discovering.

The Origins of the Varinas of Lisbon

At the end of the 18th century, the silting up of the lagoon of the Ria de Aveiro in the central region of the country completely changed the landscape and life of its inhabitants. This natural phenomenon caused the stagnation of the waters, transforming a source of subsistence and life into an unhealthy swamp. Successive epidemics reduced the population by half, and those who remained were forced to find new ways of life.

Despite an engineering intervention that solved the silting up issue in the early 19th century, the violence of the sea in those regions forced the fishermen to seek other places for sustenance. The solution was migration to the Lisbon region, first seasonally by men and later permanently with their wives and closest relatives.The 1870s brought the railroad, bringing more population to the expanding capital. This is how people from the Ria de Aveiro region, such as Ovar, Esgueira, Murtosa, Ílhavo, moved to Lisbon, bringing with them their unique way of life, traditions, and distinctive attire.

We know that these men and families settled in riverside neighbourhoods such as Madragoa, Santos, or Alfama, where they found precarious and cheap housing, living poorly on mats on the floor.

They formed a closed community that intermarried, thus keeping their traditions ingrained. They relied on the support of their fellow countrymen who had arrived first and the older women who took care of the younger children. In the absence of this assistance, babies accompanied their mothers to the Ribeira and were transported in their own baskets. Around the age of ten, children began to work, often already on their own.

Get to know Lisbon’s historic neighbourhoods in a guided tour and discover unmissable places of this magnificent city.

Ovarinos, Varinos and Varinas

Regardless of their place of origin, these men and women were called “ovarinos,” from Ovar. Over time, the name was shortened, and the “O” dropped, becoming known as “varinos” (male) and “varinas” (female).

“Varino” was also a type of boat from the Ria de Aveiro that sailed the Tagus River alongside boats, frigates, and many other traditional vessels.

“Varinos” also referred to a kind of sleeveless cape that men wore, a model that protected them from the cold without hindering their movements.

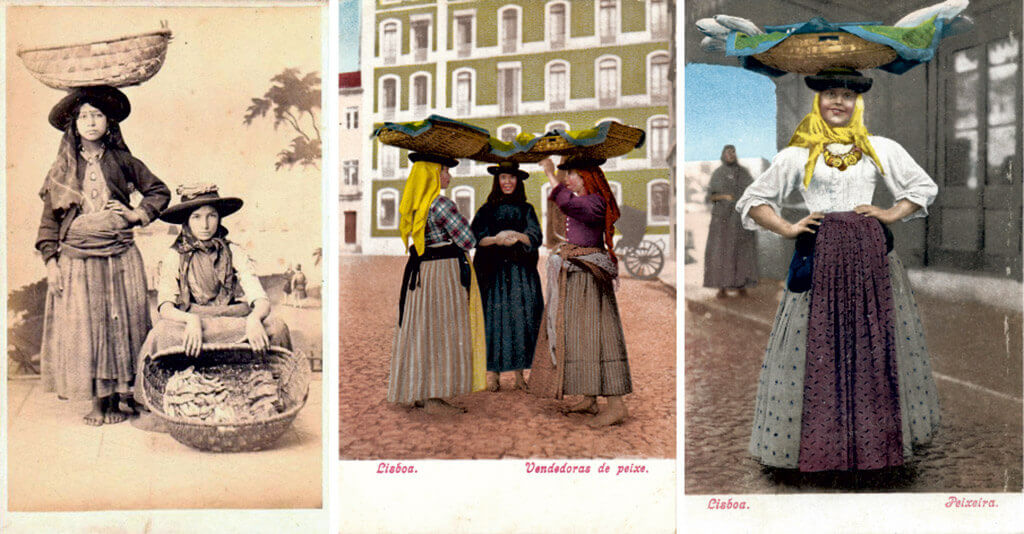

Their Unique Attire

The typical costumes of the fishwives consisted of brightly coloured blouses, lined or chequered skirts, aprons, from which hung a felt bag (patrona) for keeping money, and a mesh band on the hip that allowed lifting the skirt when necessary. They also wore a flowery scarf and a black felt hat on which they placed the “sogra”, a cloth circle on which rested the basket. These costumes, paired with the relaxed behaviour of unapologetically occupying the space of the street without asking for permission, created a certain exoticism that Lisbon residents learned to tolerate and tourists appreciated.

Varinas of Lisbon

Lisbon was the major centre for selling fish caught in northern areas like Peniche and Ericeira and southern areas like Sesimbra and Setúbal. The men from the Ria de Aveiro region might not have attracted much attention; they were just more manual labourers adding to the city’s population. However, with the arrival of their wives, the scene changed. It was impossible to remain indifferent to the cries announcing “fresh fish from the coast!”, the less appropriate language for women, the colourful clothes, skirts revealing bare legs and bare feet.

Elegant and bourgeois Lisbon reacted with astonishment and some disdain to these women who walked the streets of the neighbourhoods proclaiming hake, mackerel, mullet, haddock, and whatever else their men had brought in the early morning on the boats that docked at the Ribeira. It was still night when the fishwives arrived, barefoot in the cold waters of the river, and then took over the streets carrying heavy baskets covered with tarps.

But the fishwives didn’t just sell fish; they also ran all day back and forth on a thin plank unloading all kinds of products from the boats to the dock. Salt, coal, vegetables, cereals… a very hard job that they carried out with elegance and pride, a posture demanded by the heavy loads they carried on their heads.

| Never miss another article | Subscribe here |

Challenges and Difficulties

The fact that they walked barefoot hindered the image that the authoritarian government after the May 28, 1926 coup wanted to present externally. Thus, in 1928 and in the name of civility, it was prohibited to walk barefoot in the city, which posed a problem for the varinas of Lisbon. Besides being an extra expense, the mules slowed them down and became another reason for conflict with law enforcement. Irreverent, the women circumvented the problem by sharing the mules. When they spotted a police officer, they would sit down, leaving one foot bare covered by the skirts and displaying the mandatory mule on the other.

These warrior women faced their fate whenever they could, inevitably creating conflicts, brawls, arguments, and shouting with the public, the police, and even among themselves. However, they quickly moved on, continuing their work because hunger pressed, and there was no time to lose.

The fishwives couldn’t stop or set up a fixed stall on the street; that would compete with shopkeepers who would immediately complain to the authorities to defend their rights. They were accused of hindering the flow of people and traffic and responsible for the remains of fish gutting and the stench they caused in the city streets. Thus, they were condemned to roam the streets proclaiming and calling out to customers.

As time passed, everything changed. In the last quarter of 1980, the last fish unloading took place in Ribeira. The fishwives were destined to disappear but continue to be present in various representations: sculptures, murals, paintings, and tiles, in the songs we hum during the popular saints’ festivals, in the lyrics of fado, in the cultural imaginary of the city and its population.

All the images illustrating this article were kindly provided by the collector Luís Bayó Veiga. These are illustrated postcards that circulated in the 20th century, many of which depict the varinas of Lisbon.

The project getLISBON has been very rewarding and we want to continue revealing the singularities of fascinating Lisbon.

Help us keep this project alive!

By using these links to make your reservations you’ll be supporting us. With no extra costs!

• Looking for a different experience? We can create a customised itinerary based on your interests. Contact us!

• Or if you prefer tours and other activities in various destinations, take a look at GetYourGuide.

• Save time and money with a flexible Lisbon Card!